QU Fengguo: Corn Rain: Solo Exhibition

Past exhibition

Overview

Qu Fengguo: Paintings that Contain the Power of the Cosmos

Qu Fengguo was selected as one of the artists at the Shanghai Biennale when I was one of its curators in 2000. At the time, he had just turned 30.

That Shanghai Biennale accomplished two goals within the big picture of contemporary art in China. First, it brought contemporary art to the Mainland, so that it could be freely viewed by people in China. It seems incredible nowadays, but the art scene in China was quite conservative at the time.

Our other goal was to introduce contemporary Chinese art to the world. Since that Shanghai Biennale, contemporary Chinese art has stepped onto the world stage, growing into the flourishing spectacle of today.

Qu Fengguo was part of that wave of change. He was one of the young artists we hoped would create a new era for contemporary art in China, and the artist fully responded and lived up to the anticipation.

Here, I take into consideration the fact that the history of abstract painting lies in the background of Qu Fengguo’s art, so let us examine that background.

Abstract art is a form of expression manifested in painting and sculpture, represented by early 20th century artists such as Kandinsky, Malevich, Kupka, Mondrian, and Tatlin. The seeds they sowed flourished in the post-war period of the 1950s; overnight, it seemed abstract art had taken the world by storm.

One such artist was Chinese painter Wu Dayu. He went to Paris during the 1920s, and was exposed to abstract painting in that city. He returned to Shanghai in the late 20s, and passed on his knowledge to later generations. However, the establishment of the New China in the 1950s transformed art into a vehicle for communicating the new government’s political messages rather than a medium for expressing personal, internal worlds. It should come as no surprise that abstract art did not appear in any sun-drenched area of China’s artistic landscape during that time.

Zhao Wuji personally experienced the abstract art whirlwind of the 1950s. Following his studies at an art institute in Hangzhou, he went to Paris in 1948 and underwent the baptism of the Art Informel movement of the 50s. Later, he journeyed to the US, becoming close with a number of abstract artists, but his direct interactions with China did not occur until much later.

So-called abstract painting is an extreme manifestation of an artist’s internal world. On some level, anyone with a “story” is able understand the meaning of a figurative painting. However, the content expressed in abstract art originates wholly from the individual artist, and returns to the individual artist. There is no element of literary interpretation or story, and is extremely modern. In other words, it is a form of expression unique to modern society which formed when a set of individuals broke away from the conventional collective.

A revival of abstract painting took place in China during the 1980s. Following the Cultural Revolution, Wu Dayu’s works were first exhibited in Shanghai in 1982. The show’s influence gradually permeated the young, creative people of the time. When asked about his influences, it is only natural that Wu Dayu’s great name was mentioned in the list of Qu Fengyu’s list of artistic influences.

Taking over as curator of the Shanghai Art Museum during the latter part of the 90s, Li Xu convened abstract artists for group exhibitions at the museum; since 2001, he has begun to regularly introduce abstract artists in this way. In the exhibition literature for the museum’s second “Metaphysics” exhibition in 2002, Li Xu writes, “Shanghai is China’s capital of abstract art”. Shanghai is a nexus of individualism because this city launched the development of modern commerce in one fell swoop by introducing national capitalism during the early 20th century, giving modern individualism an opportunity to enter, and building a foundation for abstract painting.

This is the type of environment in which Qu Fengguo lives.

The artist’s work in abstract painting began around 1990. He studied production design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy – a school which happened to give rise to several talented contemporary artists including Cai Guoqiang. I imagine, perhaps because Qu and his peers felt free to study art in the theatre academy as they were unencumbered by conservative artistic traditions in such an environment. Qu Fengguo graduated from the Shanghai Theatre Academy in 1988.

During his student years, Qu Fengguo focused on painting landscapes, and began painting in a non-figurative form expressed across entire canvases around 1990.

Qu Fengguo’s student years took place during the 1980s – a period of agitation for Chinese art. This time period was not only intense in artistic spheres, the entirety of Chinese society was undergoing turmoil. The Cultural Revolution ended in 1977, information from overseas began as a trickle and quickly became a torrent; all sorts of artistic genres and styles – from French classicism to the Impressionists to Picasso – were introduced in one stroke. Thus the “New Wave Movement” took hold, reaching its peak with the “China Avant-Garde Exhibition” held at the National Art Museum of China in February, 1989. When Xiao Lu fired her gun during that exhibition, the chaos that ensued did not have a significant impact on the overall trajectory of art in China. Art became freer, and artists continued to press forward on their journeys of self-exploration.

It was during this time that Qu Fengguo abandoned art as reproduction. He came to believe that the goal of art was not to imitate the visible world. Qu Fengguo began to explore his subjects before painting them, treating them as mysteries, exploring what he was painting, discovering the essence of his subjects.

During this time, Qu Fengguo was often reading works by Nietzsche. Rather than sight, he began to believe that art should rely on the imagination – a state of mind only achievable after mobilizing both rationality and sensibility. Needless to say, artists are perceptual creatures, perhaps they lack rationality, and reading Nietzsche is a possible method for training this aspect.

In his early work with abstract painting, Qu Fengguo’s style brought paint to a boiling point on a chaotic canvases; this constituted the foundation for his subsequent works. Overall, the artist’s paintings have always contained elements of chaos; he recognizes the existence of that chaotic world, and imparts order upon it. This may well be what the artist has been laboring over since the early 1990s.

When I see his charcoal pieces from the 1990s, I recall the Ju Ran paintings I saw at Taipei’s National Palace Museum. Those were magnificent shan shui paintings of such majestic scale that if I moved in close to the glass so that only a small portion of the paintings were in my field of view, what I saw before me resembled chaotic abstract paintings. Because the paintings themselves were somber, the dimly lit atmosphere of the exhibition rooms further elicited that sense of chaos.

In fact, Ju Ran’s paintings only became shan shui paintings because the artist brought order to the chaos. Of course, Qu Fengguo’s practice is utterly different from Ju Ran’s, but similarities remain between the two artists.

Take the artist’s “The World Itself” series for example. The themes of this series are time and space. The world is formed of time and space. In Qu Fengguo’s paintings, land is subsumed by amorphous, uncontained flows of diluted acrylic paint, which mix naturally with other painting materials through movements of the canvas until an image composed of curved lines is on the brink of forming. These works are not the result of the artist’s autonomous intent, as the paint relied on the indefinite caprices of water to form the images. Water is filled with the material of the universe, ever-changing, and often chaotic; it holds the true, and dynamic nature of the world, and Qu Fengguo’s paintings captured an instant – one gesture in a series of movements.

Yet man cannot be sustained in chaos, he cannot repress his desire to give it order. Order is evidence of man’s existence. Qu Fengguo gives order to a chaotic universe by drawing lines, attempting to plainly demonstrate the existence of humanity.

The line became the protagonist of the artist’s “Four Seasons” series. This series was an attempt to transfer time to the canvas and affix it there. Earth’s four seasons move in a constant cycle within a rapidly changing universe. The metamorphosis of all things is reflected in the artist’s use of color, they embody not only changes in light, but also in substance.

Each of the four seasons was assigned an associated color: winter is black, summer is red, spring is a bluish green, and autumn is light yellow. These four colors form Qu Fengguo’s basic palette, but the colors are constantly shifting and flowing into each other in his paintings. Moreover, the countless colors are presented in lines formed after chaos is resolved.

Each time Qu Fengguo painted a line, he extended it vertically, then destroyed and eliminated the line itself before adding another on top of it. Line after line was painted on top of the previous lines which existed and were then destroyed. Lines at the surface of the paintings lie on top of the chaos of the universe. Seasons are affected by of diverse elements including light, air, land, vegetation, cities, earth, and the oceans. All of the various elements which form the phenomenon of seasonal changes are reflected in Qu Fengguo’s paintings, though the rectangular canvas is limited, an infinity of time and space extends beyond the restrictions of the frame.

After viewing a number of Qu Fengguo’s painting in the studio, I was reminded of Dong Qichang’s exposition on the necessary “vividness and vitality” of literati paintings in “Notes from the Painting-Meditation Studio”. Xie He originally gave voice to this idea, classifying “vividness and vitality” as the cardinal principle of painting.

If “vividness and vitality” refers to the sublime rhythm of the universe, then Qu Fengguo’s paintings meet this criterion. According to Dong Qichang, such energy emanates from within the artist, and Qu Fengguo has inherited this great Chinese tradition.

As mentioned before, abstract painting is an expression of the artist’s internal world, but Qu Fengguo’s abstract paintings have transcended the realm of the individual, and tapped into the rhythm of the universe. His abstract paintings are akin to shan shui paintings. In other words, shan shui paintings are akin to abstract paintings.

Shan shui paintings do not depict actual landscapes; while they are “guided by nature” (Dong Qichang), they also describe the patterns of the universe. They are distinct from the western European tradition of realism, and do not imitate nature; they merely borrow images from nature; the paintings exist only within themselves, and constitute an independent virtual space.

Founder of the 1950s “Gutai group” in Japan, Jiro Yoshihara has also spoken about the clear distinction between Japanese and western abstract painting. According to Yoshihara’s “Gutai Manifesto”, western abstract paintings face inward, while the Gutai group’s members tried to let the matter speak for themselves. Here, matter refers to nature. By transcending personal significance, the power of the universe could be channeled into the artist, which then brought forth their paintings.

In other words, although abstract paintings are an expression of an individual’s internal aspect, it would be more accurate to say that in addition to Qu Fengguo’s internal sense of “vividness and vitality”, it was his access to an unfettered spiritual environment which allowed him to tap into the energy of the cosmos and create paintings that manifest such individuality.

After the Cultural Revolution, the road has finally led past the volume of contemporary Chinese art following the 1990s to Qu Fengguo’s paintings, at last bringing us this artist who uses modern techniques to express traditional Chinese spiritual and cultural values. Shanghai is certainly fertile ground for cultivating such painters.

Spring, 2015

Toshio Shimizu (Art Critic, Professor at Gakushuin Women's College Post Graduate School)

Translation from Japanese to Simplified Chinese: Alla Zhang

Translation from Simplified Chinese to English: Fei Wu

Qu Fengguo was selected as one of the artists at the Shanghai Biennale when I was one of its curators in 2000. At the time, he had just turned 30.

That Shanghai Biennale accomplished two goals within the big picture of contemporary art in China. First, it brought contemporary art to the Mainland, so that it could be freely viewed by people in China. It seems incredible nowadays, but the art scene in China was quite conservative at the time.

Our other goal was to introduce contemporary Chinese art to the world. Since that Shanghai Biennale, contemporary Chinese art has stepped onto the world stage, growing into the flourishing spectacle of today.

Qu Fengguo was part of that wave of change. He was one of the young artists we hoped would create a new era for contemporary art in China, and the artist fully responded and lived up to the anticipation.

Here, I take into consideration the fact that the history of abstract painting lies in the background of Qu Fengguo’s art, so let us examine that background.

Abstract art is a form of expression manifested in painting and sculpture, represented by early 20th century artists such as Kandinsky, Malevich, Kupka, Mondrian, and Tatlin. The seeds they sowed flourished in the post-war period of the 1950s; overnight, it seemed abstract art had taken the world by storm.

One such artist was Chinese painter Wu Dayu. He went to Paris during the 1920s, and was exposed to abstract painting in that city. He returned to Shanghai in the late 20s, and passed on his knowledge to later generations. However, the establishment of the New China in the 1950s transformed art into a vehicle for communicating the new government’s political messages rather than a medium for expressing personal, internal worlds. It should come as no surprise that abstract art did not appear in any sun-drenched area of China’s artistic landscape during that time.

Zhao Wuji personally experienced the abstract art whirlwind of the 1950s. Following his studies at an art institute in Hangzhou, he went to Paris in 1948 and underwent the baptism of the Art Informel movement of the 50s. Later, he journeyed to the US, becoming close with a number of abstract artists, but his direct interactions with China did not occur until much later.

So-called abstract painting is an extreme manifestation of an artist’s internal world. On some level, anyone with a “story” is able understand the meaning of a figurative painting. However, the content expressed in abstract art originates wholly from the individual artist, and returns to the individual artist. There is no element of literary interpretation or story, and is extremely modern. In other words, it is a form of expression unique to modern society which formed when a set of individuals broke away from the conventional collective.

A revival of abstract painting took place in China during the 1980s. Following the Cultural Revolution, Wu Dayu’s works were first exhibited in Shanghai in 1982. The show’s influence gradually permeated the young, creative people of the time. When asked about his influences, it is only natural that Wu Dayu’s great name was mentioned in the list of Qu Fengyu’s list of artistic influences.

Taking over as curator of the Shanghai Art Museum during the latter part of the 90s, Li Xu convened abstract artists for group exhibitions at the museum; since 2001, he has begun to regularly introduce abstract artists in this way. In the exhibition literature for the museum’s second “Metaphysics” exhibition in 2002, Li Xu writes, “Shanghai is China’s capital of abstract art”. Shanghai is a nexus of individualism because this city launched the development of modern commerce in one fell swoop by introducing national capitalism during the early 20th century, giving modern individualism an opportunity to enter, and building a foundation for abstract painting.

This is the type of environment in which Qu Fengguo lives.

The artist’s work in abstract painting began around 1990. He studied production design at the Shanghai Theatre Academy – a school which happened to give rise to several talented contemporary artists including Cai Guoqiang. I imagine, perhaps because Qu and his peers felt free to study art in the theatre academy as they were unencumbered by conservative artistic traditions in such an environment. Qu Fengguo graduated from the Shanghai Theatre Academy in 1988.

During his student years, Qu Fengguo focused on painting landscapes, and began painting in a non-figurative form expressed across entire canvases around 1990.

Qu Fengguo’s student years took place during the 1980s – a period of agitation for Chinese art. This time period was not only intense in artistic spheres, the entirety of Chinese society was undergoing turmoil. The Cultural Revolution ended in 1977, information from overseas began as a trickle and quickly became a torrent; all sorts of artistic genres and styles – from French classicism to the Impressionists to Picasso – were introduced in one stroke. Thus the “New Wave Movement” took hold, reaching its peak with the “China Avant-Garde Exhibition” held at the National Art Museum of China in February, 1989. When Xiao Lu fired her gun during that exhibition, the chaos that ensued did not have a significant impact on the overall trajectory of art in China. Art became freer, and artists continued to press forward on their journeys of self-exploration.

It was during this time that Qu Fengguo abandoned art as reproduction. He came to believe that the goal of art was not to imitate the visible world. Qu Fengguo began to explore his subjects before painting them, treating them as mysteries, exploring what he was painting, discovering the essence of his subjects.

During this time, Qu Fengguo was often reading works by Nietzsche. Rather than sight, he began to believe that art should rely on the imagination – a state of mind only achievable after mobilizing both rationality and sensibility. Needless to say, artists are perceptual creatures, perhaps they lack rationality, and reading Nietzsche is a possible method for training this aspect.

In his early work with abstract painting, Qu Fengguo’s style brought paint to a boiling point on a chaotic canvases; this constituted the foundation for his subsequent works. Overall, the artist’s paintings have always contained elements of chaos; he recognizes the existence of that chaotic world, and imparts order upon it. This may well be what the artist has been laboring over since the early 1990s.

When I see his charcoal pieces from the 1990s, I recall the Ju Ran paintings I saw at Taipei’s National Palace Museum. Those were magnificent shan shui paintings of such majestic scale that if I moved in close to the glass so that only a small portion of the paintings were in my field of view, what I saw before me resembled chaotic abstract paintings. Because the paintings themselves were somber, the dimly lit atmosphere of the exhibition rooms further elicited that sense of chaos.

In fact, Ju Ran’s paintings only became shan shui paintings because the artist brought order to the chaos. Of course, Qu Fengguo’s practice is utterly different from Ju Ran’s, but similarities remain between the two artists.

Take the artist’s “The World Itself” series for example. The themes of this series are time and space. The world is formed of time and space. In Qu Fengguo’s paintings, land is subsumed by amorphous, uncontained flows of diluted acrylic paint, which mix naturally with other painting materials through movements of the canvas until an image composed of curved lines is on the brink of forming. These works are not the result of the artist’s autonomous intent, as the paint relied on the indefinite caprices of water to form the images. Water is filled with the material of the universe, ever-changing, and often chaotic; it holds the true, and dynamic nature of the world, and Qu Fengguo’s paintings captured an instant – one gesture in a series of movements.

Yet man cannot be sustained in chaos, he cannot repress his desire to give it order. Order is evidence of man’s existence. Qu Fengguo gives order to a chaotic universe by drawing lines, attempting to plainly demonstrate the existence of humanity.

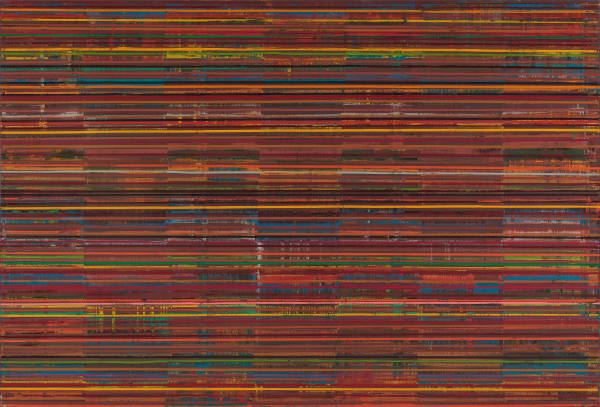

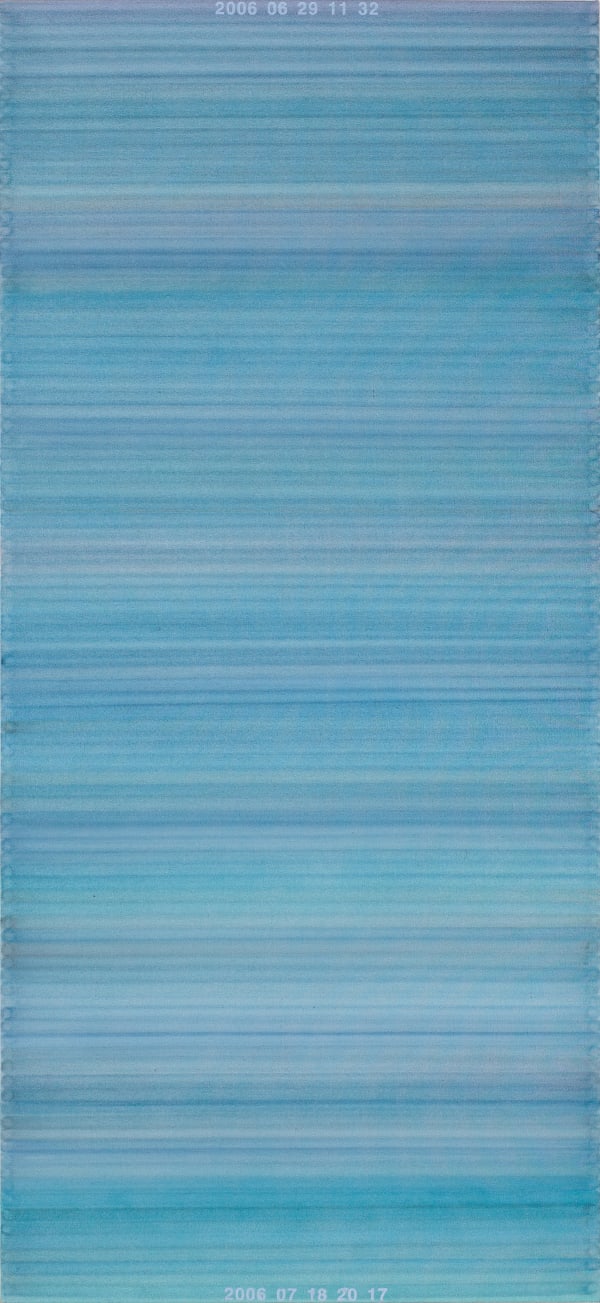

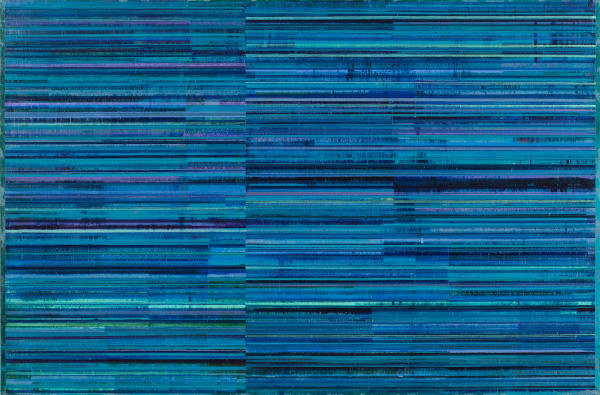

The line became the protagonist of the artist’s “Four Seasons” series. This series was an attempt to transfer time to the canvas and affix it there. Earth’s four seasons move in a constant cycle within a rapidly changing universe. The metamorphosis of all things is reflected in the artist’s use of color, they embody not only changes in light, but also in substance.

Each of the four seasons was assigned an associated color: winter is black, summer is red, spring is a bluish green, and autumn is light yellow. These four colors form Qu Fengguo’s basic palette, but the colors are constantly shifting and flowing into each other in his paintings. Moreover, the countless colors are presented in lines formed after chaos is resolved.

Each time Qu Fengguo painted a line, he extended it vertically, then destroyed and eliminated the line itself before adding another on top of it. Line after line was painted on top of the previous lines which existed and were then destroyed. Lines at the surface of the paintings lie on top of the chaos of the universe. Seasons are affected by of diverse elements including light, air, land, vegetation, cities, earth, and the oceans. All of the various elements which form the phenomenon of seasonal changes are reflected in Qu Fengguo’s paintings, though the rectangular canvas is limited, an infinity of time and space extends beyond the restrictions of the frame.

After viewing a number of Qu Fengguo’s painting in the studio, I was reminded of Dong Qichang’s exposition on the necessary “vividness and vitality” of literati paintings in “Notes from the Painting-Meditation Studio”. Xie He originally gave voice to this idea, classifying “vividness and vitality” as the cardinal principle of painting.

If “vividness and vitality” refers to the sublime rhythm of the universe, then Qu Fengguo’s paintings meet this criterion. According to Dong Qichang, such energy emanates from within the artist, and Qu Fengguo has inherited this great Chinese tradition.

As mentioned before, abstract painting is an expression of the artist’s internal world, but Qu Fengguo’s abstract paintings have transcended the realm of the individual, and tapped into the rhythm of the universe. His abstract paintings are akin to shan shui paintings. In other words, shan shui paintings are akin to abstract paintings.

Shan shui paintings do not depict actual landscapes; while they are “guided by nature” (Dong Qichang), they also describe the patterns of the universe. They are distinct from the western European tradition of realism, and do not imitate nature; they merely borrow images from nature; the paintings exist only within themselves, and constitute an independent virtual space.

Founder of the 1950s “Gutai group” in Japan, Jiro Yoshihara has also spoken about the clear distinction between Japanese and western abstract painting. According to Yoshihara’s “Gutai Manifesto”, western abstract paintings face inward, while the Gutai group’s members tried to let the matter speak for themselves. Here, matter refers to nature. By transcending personal significance, the power of the universe could be channeled into the artist, which then brought forth their paintings.

In other words, although abstract paintings are an expression of an individual’s internal aspect, it would be more accurate to say that in addition to Qu Fengguo’s internal sense of “vividness and vitality”, it was his access to an unfettered spiritual environment which allowed him to tap into the energy of the cosmos and create paintings that manifest such individuality.

After the Cultural Revolution, the road has finally led past the volume of contemporary Chinese art following the 1990s to Qu Fengguo’s paintings, at last bringing us this artist who uses modern techniques to express traditional Chinese spiritual and cultural values. Shanghai is certainly fertile ground for cultivating such painters.

Spring, 2015

Toshio Shimizu (Art Critic, Professor at Gakushuin Women's College Post Graduate School)

Translation from Japanese to Simplified Chinese: Alla Zhang

Translation from Simplified Chinese to English: Fei Wu

Works

-

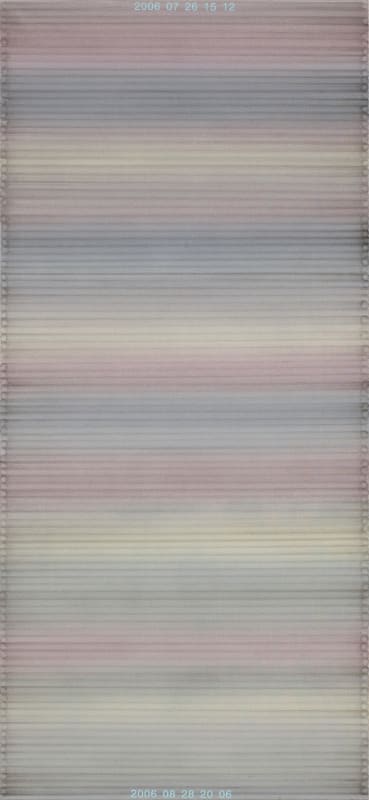

QU Fengguo200607261512 200608282006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉250 x 115 cm

QU Fengguo200607261512 200608282006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉250 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm -

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题 2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题 2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoMidsummer, Four Seasons 四季 仲夏, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 210 cm

QU FengguoMidsummer, Four Seasons 四季 仲夏, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 210 cm -

QU FengguoSummer, Four Seasons 四季 夏, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm

QU FengguoSummer, Four Seasons 四季 夏, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm -

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm

QU FengguoAutumn, Four Seasons 四季 秋, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm -

QU FengguoWinter, Four Seasons 四季 冬, 2013Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm

QU FengguoWinter, Four Seasons 四季 冬, 2013Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm -

QU FengguoWinter Commences 1, Four Seasons 四季 立冬 1, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm

QU FengguoWinter Commences 1, Four Seasons 四季 立冬 1, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoWinter Commences 2, Four Seasons 四季 立冬 2, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm

QU FengguoWinter Commences 2, Four Seasons 四季 立冬 2, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoWinter, Four Seasons 四季 冬, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm

QU FengguoWinter, Four Seasons 四季 冬, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画110 x 140 cm -

QU FengguoModerate Cold, Four Seasons 四季 小寒, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画80 x 100 cm

QU FengguoModerate Cold, Four Seasons 四季 小寒, 2012Oil on Canvas 布面油画80 x 100 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 1 无题 1, 2007Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀180 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 1 无题 1, 2007Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀180 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题 2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2006 无题 2006, 2006Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm -

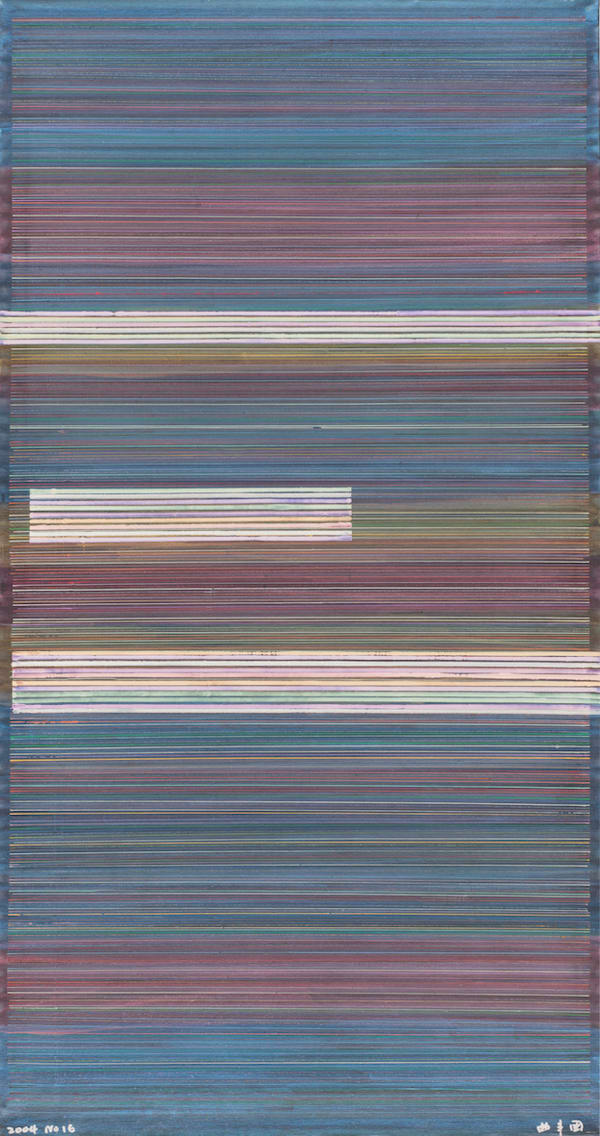

QU FengguoUntitled 2004 16 无题 2004 16, 2004Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉200 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2004 16 无题 2004 16, 2004Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉200 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀220 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀220 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic and Charcoal on Canvas 布面丙烯和碳粉220 x 115 cm -

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀115 x 220 cm

QU FengguoUntitled 2005 无题2005, 2005Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙稀115 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2015Oil on Canvas 布面油画120 x 120 cm

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2015Oil on Canvas 布面油画120 x 120 cm -

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2014Oil on Canvas 布面油画145 x 220 cm -

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm

QU FengguoSpring, Four Seasons 四季 春, 2006Oil on Canvas 布面油画210 x 310 cm