Drawing and drawing: Heading out and Bending down. Dual exhibition of LI Shan and Kumi Usui: Dual Exhibition

Drawing and drawing: Heading out and Bending down On dual exhibition of LI Shan and Kumi Usui

by Wang Kaimei

In the autumn of 1975, LI Shan, recently turned 18, travelled from Beijing to Beidaihe to sketch outdoors. Accompanying her were several more experienced older art enthusiasts who had introduced her to the world of art. Having grown up in Beijing’s iconic hutong, - small lane, it was the first time that LI encountered with the Pacific Ocean. Facing the blue storming sea, LI Shan found herself struck speechlessly with exhilaration. She pulled out her homemade artist’s kit and started to depict the crashing waves colliding towards the sky, which in her eyes looked like a sea of white rice popcorn.

Throughout the 1970s, LI Shan cultivated a daily routine of sketching outdoors with her art kit. Later, she became the youngest member of the “No Name Group,” an underground artists group consisting of many art enthusiasts in Beijing. The members wandered through the city’s parks drawing mountains and trees, sunsets over the red walls, and reflection of the white pagoda, typical sceneries of Beijing’s parks. At the time when the only sanctioned aesthetic involved portraits painted in rigorous socialism realism style, and landscapes and nature were only relegated to the background of revolutionary images, what LI Shan and her friends did - heading out and sketching outdoors, were not only an act of avant-garde, it was also a risky gesture.

Meanwhile, in a small town on the Pacific coast in Japan’s northeast, an 8-year-old girl called Kumi Usui was attending a calligraphy class taught by her father, alongside with hundreds of children from near and far. For the young Kumi Usui, each brushstroke seemed to elicit a vague emotion and understanding. When she was in junior school, an art teacher returned from France enlightened her about art, by the time she entered high school, she had decided to become an artist. On each school vocation, Kumi would ride the train to Tokyo for a whole night in order to attend a cram school for art exam. Her peers at the cram school included students who had failed to pass the exam in previous years. Their conversations about art and the artist’s purpose gave Kumi a new understanding of the profession. In 1988, she was admitted to Tokyo Musashino Art University and enrolled in the Department of Oil Painting. At the time, the art education system in Japan still adhered to traditional methods of teaching techniques of painting. Presented with the option of studying either figurative or abstract painting, Kumi chose the later.

These two artists, LI Shan and Kumi Usui, who have never met each other in life, their artworks will meet for the first time in this dual exhibition.

Along with the development of the Chinese society, the “No Name Group” became an important milestone representing the pursuit for free spirit within the Chinese contemporary art in its very early stage and holds a significant place in art history today. LI Shan keeps on the habit of painting outdoors until today. The only difference is, she has been venturing further and further away from home — from Svalbard on the Arctic Sea, to New Zealand in South Pacific-- she has painted the midnight sun, snow-capped mountains, and floating glaciers on the icy water. Browsing through LI’s traveling notebook, you’d find remarks of “sitting down to draw” everywhere. In 2019, she painted a new Portrait of the Temple of Heaven.

“I can’t remember how many years ago since I last visited the Temple of Heaven...with my little painting kit, I wandered towards the Hall of Prayer for Good Harvests. I found a quiet spot, and started painting,” she recalls. By that time, her painting was much more than a representation of the scene in front of her eyes. She was trying attempting to capture the feeling of seeing the Hall once more. The painting is calm and joyful, lingering with a hint of nostalgia. The scenery becomes a thread connecting the artist back to her experience. Among the gifts of enlightenment and significance that art brings to mankind, painting outdoors brings art back to its starting point. To LI, painting is a way to record the happiness in life, or to be precise, painting is LI Shan’s happy life.

Just as the Chinese society went through drastic changes and Chinese contemporary art started to connect to the rest of the world, Kumi Usui visited China for the first time. From Yokohama to Kobe to Shanghai, Kumi’s tour in China extended from a time-limited planned vacation to an indefinite period of study abroad, and later, the artist would find love, and a place of belonging here.

Three decades later, Kumi lives and works in China. She speaks fluent Mandarin, and even Chongqing dialect. Just as she immersed herself in practice at the cram school so many years ago, she has immersed herself in painting countless abstract works, with her head bending down, she keeps on paining regardless of the boundaries and forget about causes and results. Her technique combines the gestural brushstrokes of Japanese calligraphy and the wandering style of Western abstract painting. Acrylic paint covers sheets and sheets of sketchbook sized paper.

The works are varied. Some feature a few brushstrokes, and a smattering of canny points and lines. Others are dense and passionate — covering the entire sheets with a single color, often blue. Intuition is clearly in charge here, with many brushstrokes made almost unconsciously, but what lies behind the mental engineering that guides one’s intuition and instinct? This is the question that Kumi Usui meditates upon in her artistic practice -- the essence of life, and how to create art that returns to the origin of joy, motivation, and meaning.

Landscape is the subject in LI Shan’s art, nevertheless, Kumi Usui’s intention is as well depicting her inner landscape, isn’t it? The two artists approach the Genesis Point of art from different perspectives, may it be recreating nature or imagining landscapes. Art critic John Berger once pointed out, “The region in which a painter passes his childhood and adolescence often plays an important part in the constitution of his vision. The Thames developed Turner. The cliffs around Le Havre were formative in the case of Monet. Corbet grew up in – and throughout his life painted and often returned to – the valley of the Loue on the western side of the Jura mountains.” No matter how far LI Shan’s footsteps may take her, her paintings always shine with the same light as Beijing’s parks in the 1970s. Just as the various shades of blue and the calligraphic brushstrokes in Kumi Usui’s paintings always bring her back to her hometown on the Pacific coast. Though she may have acquired a love for Chongqing’s spicy hotpot, her hometown sea will continue to echo in her paintings.

-

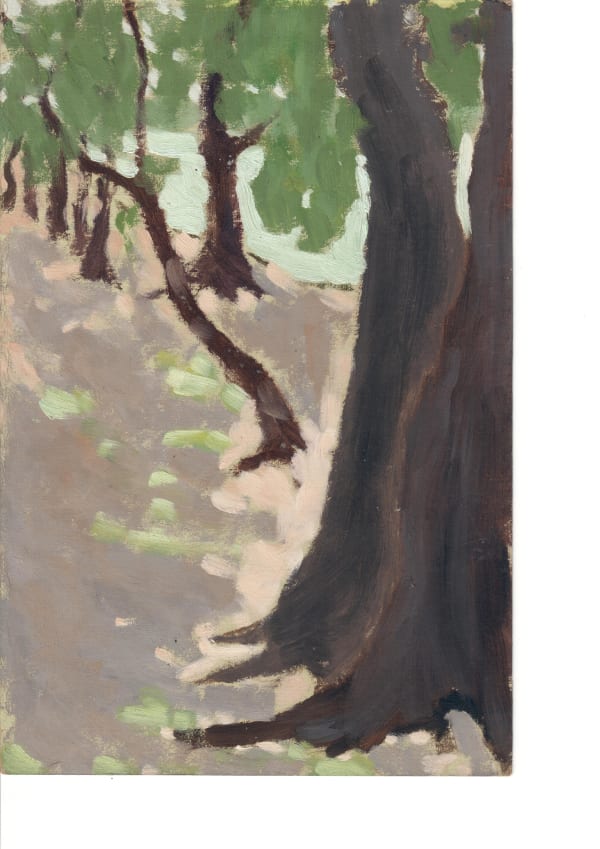

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

Framed 有画框27 x 18 cm -

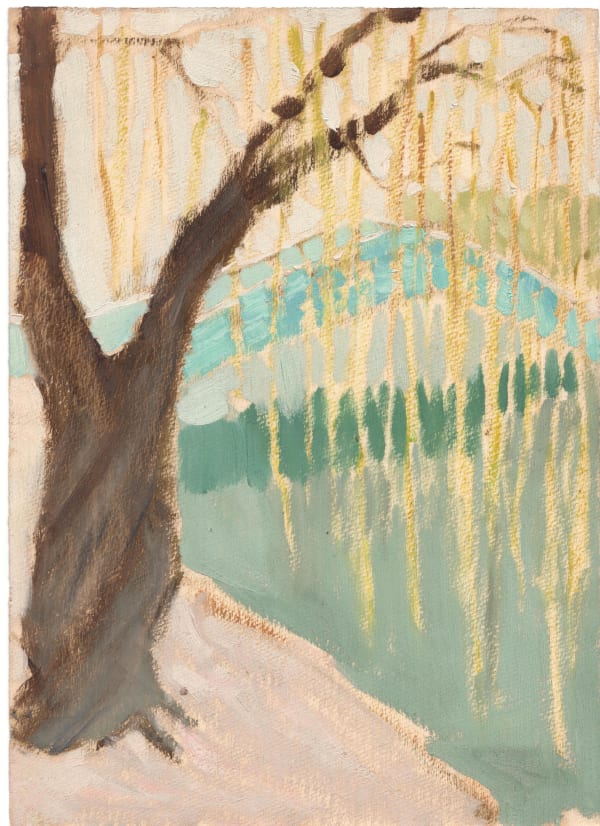

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

Framed 有画框27 x 19.5 cm -

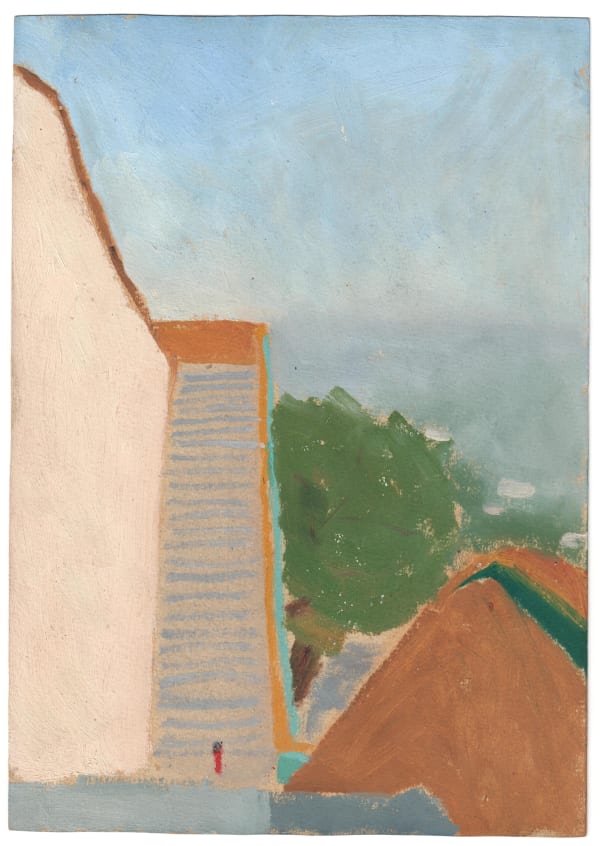

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

LI Shan 李珊Untitled 无题, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

Framed 有画框27.1 x 19.2 cm -

LI Shan 李珊Untitled (ZiXhuyuan Park) 无题 (紫竹院公园), 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

LI Shan 李珊Untitled (ZiXhuyuan Park) 无题 (紫竹院公园), 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画

Framed 有画框19.5 x 27 cm -

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(The landscape or the Remains of landscape)(on canvas) 2021 #1 埋头画画(风景或变成风景的残留)(布面)2021 #1, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯89 x 221 cm Acrylic on canvas 89 x221 cm 布面丙烯

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(The landscape or the Remains of landscape)(on canvas) 2021 #1 埋头画画(风景或变成风景的残留)(布面)2021 #1, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯89 x 221 cm Acrylic on canvas 89 x221 cm 布面丙烯 -

LI Shan 李珊When ZHANG Wei Was Sketching 正在写生的张伟, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画27 x 7.5 cm

LI Shan 李珊When ZHANG Wei Was Sketching 正在写生的张伟, 1970sOil on cardboard 纸板油画27 x 7.5 cm -

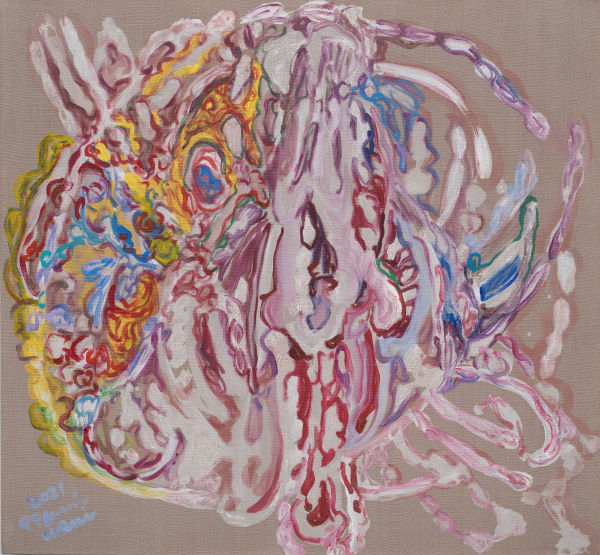

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #26 埋头画画(布面)2021 #26, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯150 x 160 cm

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #26 埋头画画(布面)2021 #26, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯150 x 160 cm -

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #4 埋头画画(布面)2021 #4, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯73 x 69 cm

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #4 埋头画画(布面)2021 #4, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯73 x 69 cm -

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #16 埋头画画(布面)2021 #16, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯70 x 65 cm

Kumi Usui 九九Drawing & Drawing(on canvas) 2021 #16 埋头画画(布面)2021 #16, 2021Acrylic on Canvas 布面丙烯70 x 65 cm