-

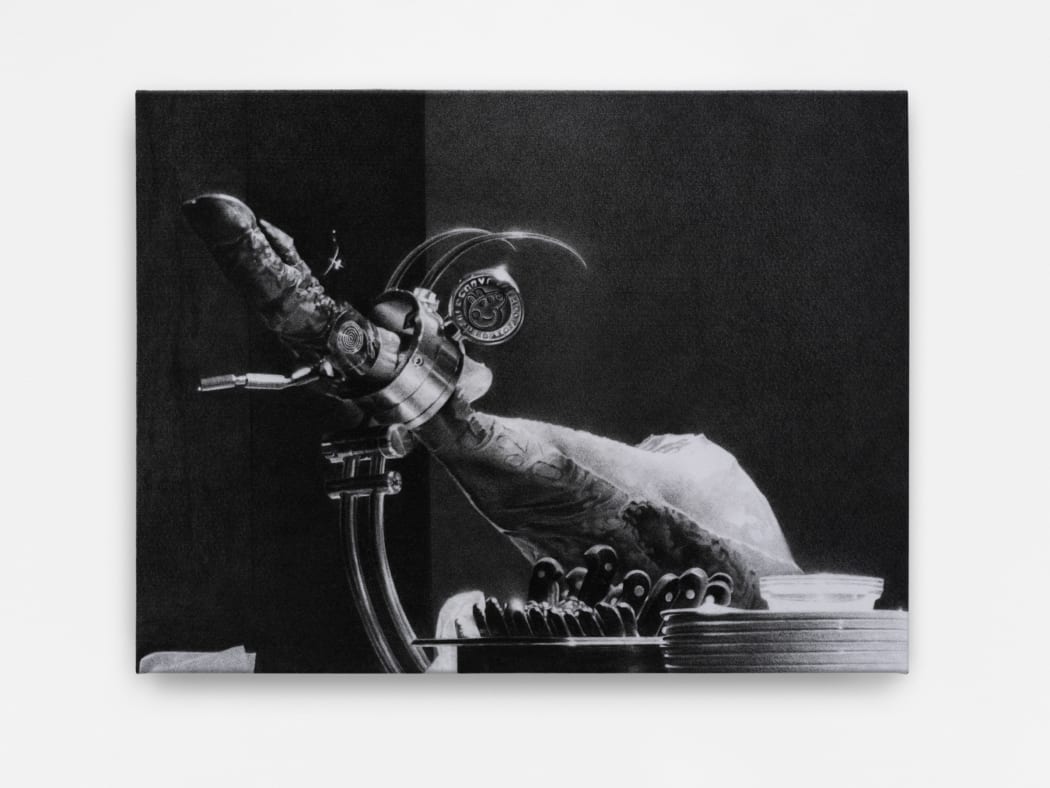

Using graphite pencils on felt, ZHANG Yunyao has developed a distinctive visual language. The artist minimizes brushstrokes and uses very little color to create an “anti-painting” approach which results in an extreme form of visual imagery. The stretched white felt is a malleable canvas, and the pencil marks appear nearly devoid of tangible material quality. Yet, astonishingly, images cling to the soft, undulating fibers, as if floating to the surface. In other painting techniques, pigments form their own surfaces through texture and thickness, merging with the canvas as the image’s physical form. However, ZHANG’s drawings present the image itself. Although forms are achieved through negative space, the entire surface has been touched by graphite, and it is all part of the image. Within the impeccable unity of space, even the untouched areas do not reveal their native texture. The artist’s approach is thoroughly rational and composed. Through this intense, unforgiving, and rigorous process, ZHANG uses an extreme range of black and white tones to eliminate most traditional painting techniques. Instead, the artist focuses on the psychological landscapes that originate from within, eschewing objects and experiences drawn from daily life. His subjects are often European sculptures portraying the human body in extremis. At times, ZHANG employs montage layering and random smudges to create a sense of multidimensional structure and spatiotemporal richness. To the artist, Ancient Greek and Baroque sculptures represent an art of fear and hope—opposing emotions manifesting as dual aspects of the same subject. The two are interdependent, hope does not exist without fear, and vice versa. In depicting these extant three-dimensional works, the artist constructs a transcendent psychological space which contrasts with the palpable atmosphere and depth of his images. Gleaming in black and white tones, bronze and marble forms seem to struggle within timelessness. Untouched by reality, they appear more real than what the eye can see.

After living in Paris for nearly half a decade, the artist’s focus shifted. ZHANG’s early art education began in drawing animals, and in Paris, the artist found his interest in animals and nature rekindled. Experimenting with stretched white felt and colored pencils, ZHANG began to introduce animals, and in particular, primates, into his work. In particular, he mentions the Musée de la Chasse et de la Nature in Paris, along with exhibitions of prints, illustrations, posters, and other works on paper. In pre-modern times, hunting was an aristocratic pastime where one killed animals in displays of courage and might. With technological advancements, the nobility were able to document their exploits in great detail. During that time period, academic disciplines were not classified as they are now. Today’s biology, geology, and ethnography were all part of “natural history,” as opposed to “natural philosophy” which encompassed physics and chemistry. As scholars embarked across the world, they returned to Europe with discoveries from the New World, and these collections of curiosities eventually evolved into the modern museum. Natural historians, then known as naturalists, sketched, painted, engraved, and taxidermied their findings—doing the work themselves or commissioning others to do it for them. Many of these image makers did not have artistic training and instead relied on instinct and experience, using their grasp of various mediums to convey the form and detail of their subjects. Their primary goal was to capture the specimen’s objective state, isolating its characteristics from the environment, and rendering it into a passive object. Non-artistic in nature, these images captured ZHANG’s imagination, and provided a fresh perspective on painting.

When sketching botanical and zoological specimens, scientists developed parallel projection techniques to capture an object in two dimensions; these techniques are also used in architectural, engineering, and mechanical drafting. Much like the way in which early humans made imprints of their bodies or created pressings of plant specimens, this image-making method consistently regards the object as an independent entity, transcending time. The object possesses fixed, immutable dimensions, shapes, and colors, which renders them available for observation, measurement, and even replication to some extent. Parallel projection became a key drafting technique and was widely applied to illustrations, manuals, emblems, advertisements, and design, and dominated a large swath of artificial image making during the pre-modern era. In Eastern traditional art, one also sees axonometric projection in the depiction of objects in space. This is a type of parallel projection that simultaneously depicts an object’s front, side, and top views, and is often seen in architectural renderings. Thus, Eastern painting tradition and pre-modern drafting techniques share a fundamental origin: observation and examination are multidimensional and fluid, focusing on the object itself, whereas the representation of said object emphasizes outcome and the effectiveness of practical application on multiple levels.

In contrast, single point perspective came to represent another facet of image making, which focused more on the optical method of image creation and its conveyed meaning. It was already present in ancient Greek and Roman painting, and the concept of “objects that are nearer are larger, while objects that are farther appear smaller” is also found in art from many other civilizations. However, it was Italian Renaissance artists who systematically developed and applied principles of single-point perspective, with Leon Battista Alberti and Piero della Francesca offering some of the most comprehensive explanations.

The idea of “objects that are nearer are larger, while objects that are farther appear smaller” was defined through mathematical and geometrical principles, from there, rules and guidelines followed. Unlike parallel projection, which only depicts the relationship between the object and the image plane, single point perspective introduces an observer who stands outside the image. The artist is the observer, and as a subjective entity, chooses a single, static viewpoint at a specific moment, and makes the near and far perspective absolute under set conditions. Conceptually speaking, single point perspective reveals the space-time relationship between the observer and the external world by capturing a single moment in the progression of time, serving as a tangible record of “here and now.” Thus, the observer interacts with the object within the context of space and time set within the entirety of the past and future, and captures this interaction through the principles of single point static image making. The aim is to preserve the interaction from time’s passage and shifts in space, enabling any individual who later encounters the image to inherit the observer’s perspective. From the creator’s perspective, once the interaction becomes an image, it begins to move into the future. From the viewer’s perspective, their interaction with the image takes them back in time, to become that same observer. The resulting image is imbued with a culturally significant “mystical moment” which comes to pass as these interactions align with the linear sequence of time. In a way, painters from the Renaissance until Impressionism were embedding personal expressions of “mystical moments” within the space-time of history.

We believe that all things, including ourselves, have a beginning and an end. And so, linear time is inevitable. Single point perspective seems to construct a perfect world that mirrors the ideal universe described by Newton’s laws of motion. The significance of single point perspective also brought realism to the forefront of visual art, and through its connection to the principles of optics, led to the invention of photography. However, modern physics has reshaped our understanding of the universe, and cognitive science has revealed that the idea of “perfect representation” is ultimately misguided. Visual information is processed subconsciously in the brain, and we construct what we think is an “objective” world. However, this perception is in fact far from objective or complete, our perception has adapted over time to meet the demands of evolutionary survival. In our contemporary understanding, we humans are not the world’s masters and our history as a species on this planet is brief. Animals are a more stable reference, and become humanity’s metaphors. This is ZHANG’s departure point and why he uses systematic drafting techniques to replace and update the perfect space formed by single point perspective. The “mystical moment” extends forwards and backwards, reaching into the depths of time, space, and consciousness. Through allegories of primates and other animals, ZHANG expands upon his artistic expression, and explores the origins of emotion with a liberated approach to painting.

Color plays a vital role in scientific illustration, and it inspired ZHANG to experiment with using colored pencils to draw on felt. Like graphite pencils, colored pencils allow for detailed work. Yet, their qualities of lighter adhesion and penetration align with the needs of scientific illustration. Unlike his previous works, ZHANG’s primate drawings feature large areas of pale objects and backgrounds. But no matter how light, the artist has meticulously covered the canvas with colored dots and lines, putting extraordinary effort into each detail. Although colored pencils come in a wide range of colors, not all of them are suitable for using on felt. Artists who are accustomed to mixing pigments will find it necessary to utilize techniques similar in principle to pointillism. ZHANG has employed methods such as juxtaposition, contrast, and interweaving to achieve rich, yet subtle color effects. In his drawings, the combination of colored pencils and felt enables an extraordinary rendering of the fine textures of plants and primate fur. This approach is comparable to the composition and execution of traditional European tapestries from which ZHANG has also drawn inspiration.

Though color selection is inherently subjective, when it came to choose colors for his drawings, ZHANG intentionally heightened and emphasized subjectivity. Scientific drawings attempt to reproduce the actual color of objects, but ZHANG’s use of color instead prioritizes psychological effect, and diverges from the object’s natural hues. His technique resembles a negative image, where he weaves objects into specific environments via color relationships. In addition to his felt paintings, the artist also created works through photographic techniques when he was in Paris. Using his phone to snap photos of animals, he later processed the images and presented the negatives as art. The animals in these images are at times unidentifiable because the inversion of positive and negative imagery results in surreal colors, creating a sense of conflict and distortion that challenges conventional perception. ZHANG is not seeking to be effective via the logic of photography. Instead, he takes a creator’s perspective, and explores his observation of the world and selects colors that “speak.” This complementary color effect, which is akin to negative imagery, has also been introduced into some of ZHANG’s felt paintings. Along with the artist’s construction of the scene, his transformation of the relationship between objects, and the altered states of the objects themselves, ZHANG has created a “Palace of Alienation” in an evolutionary sense.

In his “Palace of Alienation,” the word “alienation” refers to a generalized state of existence and awareness, which is related to the loss of subjectivity and the lack of awareness of such. The evolution of life, which includes humans, is far from peaceful; it is a mere manifestation of life’s blind resistance to that mysterious cosmic force—entropy. ZHANG’s primates exude calm and grace, yet the subjective treatment of their form and his unconventional use of color creates an atmosphere of unease and impending doom. Herein lies the paradox. On one hand, life is a divine directive, the culmination of logic. On the other hand, all living beings are merely evolution’s survivors. In this second act of the “Palace of Alienation” series, ZHANG continues using the familiar medium of graphite pencil on felt, transforming objects and scenes borrowed from specific moments in time into inexplicable souvenirs, suspended somewhere in the subconscious. And so, ZHANG commemorates the centennial of Surrealism.

One of the works titled “Palace of Alienation” was inspired by sketches the artist made during lockdown in 2020, when he was confined to his room in Paris. The piece depicts a wooden owl sculpture, overlaid with eyes borrowed from a Greek bronze. The work is infused with the dread and hope that was experienced by so many around the world during that time and also carries the “mystical moment” through the act of observation and representation. It signals the artist’s subsequent reflection on the significance of life and the act of painting. Along with this piece, ZHANG has also titled several other works metaphorically and ironically. Their titles form a dialogue with their psychological landscapes. Within this intimate and paradoxical psychological turmoil, the works coalesce as evidence of emotion, which symbolize the circumstances of the artist and his peers.

ZHANG Li, born in 1970 in Jilin, is a contemporary art curator and writer who currently resides in Shanghai.

-

A Warm Breath Set the Leaves Stirring (Commentary)

Author WANG Jiang

A warm breath set the leaves stirring. "The leaf is the lung of the tree which is itself a lung, and the wind is its breathing," Robinson thought. He pictured his own lungs growing outside himself like a blossoming of purple-tinted flesh, living polyparies of coral with pink membranes, sponges of human tissue. …He would flaunt that intricate efflorescence, that bouquet of fleshly flowers, in the wide air, while a tide of purple ecstasy flowed into his body on a stream of crimson blood…

The passage above is taken from Friday, or, The Other Island (1967) by Michel Tournier, a novel that reconstructs the Robinson Crusoe narrative as told by Daniel Defoe. The quote not only depicts a natural phenomenon but also symbolises a transition in the protagonist Robinson's perception of the natural world and himself. Robinson transforms from a rationalist to an "elemental man" who lives peacefully with nature as a result of his isolated experiences on the island. The author intends to investigate the deeper meaning of human existence as well as the conflict between civilization and wildness through the philosophical and psychological notion of the Elemental Man.

The exhibition title "A Warm Breath Set the Leaves Stirring" conveys LU Song’s exploration and contemplation of the interaction between man and nature in addition to echoing his portrayal of nature and celebration of vitality in his works. A further metaphor for LU Song's conception of artistic creation can be found in the background of the narrative that is cited. Similar to Robinson's metamorphosis in Tounier's book, LU Song's inventions reveal his ongoing investigation and understanding of the self and the outside world.

Revelation: The Elemental Man's Dream

LU Song has mentioned many times that Michel Tounier's novel Friday, or, The Other Island has inspired his paintings. Thus, we can draw a comparison between his theory of painting and the concepts found in Tounier's book. Tounier's novel, which LU Song found inspiring, chronicles the protagonist Robinson's struggle with loneliness while living on a barren island. It is a work that examines human existence, loneliness, nature, and society.

Robinson's intimate affinity with the natural world prompted LU Song to consider the profound bond between nature and humanity. His artwork captures stunning moments when a person's spirit combines with the natural world. Nature provides aesthetic value for humans. LU Song’s depiction of the distinct shapes, hues, and textures of forest flora embodies the harmony, tension, and mystique of the natural world. Natural landscapes, on the other hand, stimulate his imagination and lead him to explore novel painting shapes and methods. He emphasizes the significance of harmony between man and nature, just like Tournier does. In his paintings, nature is conducted as an enigmatic universe. The human spirit is contaminated by the depths of the forest, the cycle of life, and the force of nature. The relationship between nature and human emotions is explored in LU Song's artwork. His spiritual journey and emotional state are hosted by the branches, leaves, light, and water vapour in the photographs. The surrounding environment starts to mirror his inner world.

LU Song's empathy was aroused by the lonely story in the novel, and it's possible that his previous career experiences also provoked him to reflect carefully on loneliness, introspection, and self-discovery. For him, being alone is not just a feeling; it also serves as an inspiration for art. He acutely perceives nature's power while alone in the jungle and stares at the canvas. In solitude, LU Song gets the chance to examine his thoughts on his own. His works serve as a testament to this process and demonstrate his contemplation on existence, life, and the self. He investigates the connection between the internal and external realms. He always experiences a calm and harmony that transcends the ordinary when he is alone in nature, and he transforms this feeling into the love and spirit that he portrays in his paintings. During this process, being alone presents both a challenge and a chance for spiritual awareness and personal development. The slow process by which the visuals take shape is symbolic of the inner transformations that occur when a person experiences loneliness and is intended to unveil a deeper degree of self-awareness.

Tounier's writings investigate the nature of survival and man's transcendence in the face of tragedy, whereas LU Song’s paintings depict the force and beauty of life in nature as well as its resilience and transcendence in the eyes of man. Man and environment interact not just for survival but also for the possibility of transcending into another realm. This could be awe and respect for the force of nature, or it could be an investigation and comprehension of the meaning of existence. While LU Song does not include any human figures in his works, his point of view hides the pondering and epiphany of man in the natural world. In it, nature is the source of beauty as well as the place where everything exists. LU Song's works prove how the natural beauty of nature enhances and displays the spirit by depicting certain fragments and moments. This aesthetic encounter becomes a significant aspect of one's spiritual life and surpasses the urge for survival. Spiritual inquiry leads to the ideas of transcendence and survival.

Similar to how Tounier's novels are rife with fantasy, LU Song’s paintings conjure up dreamlike images. He creates spiritual imagery through abstraction and symbolism. Realistic aspects coexist with bizarre, illogical ones like floating plants, overlapping spaces, and impossibly constructed structures. The surrealistic expression piques the interest of the viewers and transports them to a heterogeneous world. Conversely, symbolism uses images and symbols with deeper meanings to communicate abstract ideas and feelings. The subconscious of the person is revealed by LU Song's visuals, which are full of metaphors and illusions that allude to the most profound hopes, anxieties, and wants of the human heart. His paintings occasionally have religious themes, such as elves, angels, and gods; these are as subtle as the iridescent light that hangs from branches and foliage. In addition to giving the pictures an air of mystery, these components convey how much man worships and reverence supernatural powers and the universe's order.

Exploration: Dance of Trees

"Whilst travelling through the rainforest, my eyes swept over a strange structure of whirling, flowing, curling dead leaves clinging to hidden cobwebs of discarded leaves that appeared to be suspended in the air," says LU Song, explaining the origin of the Dance of Trees series. "The background's emerald green of regeneration blends with the smell of decomposing leaves, evoking a new world that flattens time or being elegiac or joyful of that moment when the old and the new meet and coexist. The curving, floating forms of the dead leaves resemble those of a modern dancer or acrobat, showcasing the interaction between the body and space through a variety of astonishing airborne moves.”

In light of this, it is simple to comprehend LU Song’s inspiration for creating this environment as well as to picture his feelings upon first seeing it. He tells about an odd thing that captures a moment when the old and the young are alternating and coexisting. It has the aroma of rotting leaves mixed in with the green tint of fresh life. This illustrates not only the natural cycle and turnover but also the passing of time and the transience of existence, as nature and time merge to form one. LU Song uses the metaphor of the dancing leaves and branches to represent the dynamism and change of life. The investigation of this form represents the investigation of the body's relationship to space, illustrating life's quest for harmony and balance in the face of perpetual change. LU Song's attempts to depict a supernatural phenomenon and an enigmatic power in his works surely reflect his interest in the unanswered secrets of nature. As stated in his self-description, he conjures up a fanciful time and space by fusing parts of nature and human conduct to subjectively interpret natural phenomena.

There is a noticeable air of levitation in this series. One can comprehend levitation on a number of levels. LU Song uses layers and space to give the pictures a sense of visual levitation. This is seen in the arrangement of the entire image as well as in the individual objects. He creates an abstract yet traceable state of suspension by using overlapping and distinct colour blocks, lines, and brushstrokes to make each component autonomous and related at the same time. Also, feelings are the starting point for many of LU Song's compositions. He believes that valuable things are sometimes created subconsciously, a state of unconsciousness he refers to as " tipsy/slightly drunk". His inventions are not constrained by a particular thinking mode, but instead freely flow between many emotions, producing a sensation of emotional suspension. In this state, emotions are suspended between logic and irrationality. Above all, his pictures are his thoughts on the connection between life, the natural world, and art. His inspiration for creating stems from an investigation into the substance of life and the meaning of existence, which frequently bears a philosophical feeling of suspension, i.e., a situation in which the quest of truth is both difficult to get at and continually approaching.

It is important to note that LU Song's description of being "tipsy" refers to a certain psychological condition. LU Song's subconscious mentality is not constrained by reason when it comes to tipsy. As a result, he can more naturally and vividly convey his innermost ideas and feelings. Through tipsy, LU Song is able to express his feelings without interruption from others or from self-control, which facilitates his exploration of his inner self. Similar to daydreaming, tipsy can inspire original thought and disrupt ingrained thought patterns. Tipsy is a state of both relaxation and focus, despite its indulgent name. It keeps LU Song comfortable while enabling him to concentrate on his works and gain a deeper understanding of the painting process. This looseness then turns into a distinctive feature that is seen in his images.

The Dance of Trees's title, according to LU Song, was inspired by Fraser's The Golden Bough. It is an anthropological work that investigates global mythologies, religions, and folklore to show how conscious and worshipped natural and supernatural entities have been by humans. The viewpoint presented in the book, in my opinion, may be applied just as well to LU Song’s paintings. It describes a universe in which humans interact with the natural and supernatural realms through a variety of customs and beliefs. LU Song’s artwork portrays a comparable interaction. Notably, the book makes reference to a type of "mistletoe" that the aboriginal tribesmen consider to be the most spiritual plant on earth. It is parasitic on other trees, not rooted in either place, and it transcends the physical world, much like the leaves and branches that appear to be floating in LU Song's paintings. They all represent humanity's quest for transcendence.

Intertwined: Temptation and Danger

Marron Hugger reveals a sense of danger in contrast to the Dance of Trees‘s joy. LU Song attempts to hint at the harsh laws of nature by drawing the flytrap. I say "hints" because LU Song's technique of drawing the flytrap is very literal; the combination of eyelash-like lines has a feminine elegance, but the lines' power and stance also make a strong statement. The stylized design makes it challenging for the viewer to quickly recognise the flytrap image, yet it is simple to understand the emotion it conveys. Red hues with varying warm and cool undertones overlap each other on the screen; before they meet, they have been mixed and thinned to differing transparency. Consequently, certain areas of the colour have a unique haziness and lightness. The cautionary connotation of the colour red adds to the tension created by this emotion.

Unquestionably, the flytrap is a secretive topic for painting. The edges of its leaves extend regular soft spines in the form of eyelashes. Its short-term memory can last for approximately 30 seconds. If an insect taps on its stinging hairs, the flytrap will not respond right away; however, if the insect touches it again within 30 seconds, the flytrap will close its blades and kill its prey. This is why it is also known as the "Venus Flytrap". Natural selection and the survival of the fittest are reflected in its short memory and the certain end of its prey. Since mimicry and camouflage are common in nature, the flytrap's colours and patterns both draw in their victims and pique their curiosity. Peril and desire are akin to opposing sides of one coin. There are always unknown risks involved with living a life driven by desires. This series of works specifically conveys the idea that life finds inspiration in the facts and laws of nature.

I was drawn to Marron Hugger's eyelash-like shapes when I first saw them. LU Song referred to them as "guiding bridges" and failed to provide a clear explanation when I questioned what they were used for. Occasionally, the figurative term "guiding bridges" appears in LU Song’s language. He coined the phrase to characterize the components or methods that help viewers understand a piece of art's deeper significance. LU Song has explained things using the narrative form of Junichiro Tanizaki's novel蘆刈(Ashikari; later: The Reed Cutter, 1948). In this book, the true turning point of the tale is concealed beneath the surface of the story, and the author leads the reader there with a succession of illustrative details and plot points. The reader can traverse from the story's surface level into the depths of the concealed meaning with the aid of these illustrative clues and storylines. LU Song, in contrast, employs this idea in his paintings, where specific images, hues, and brushstrokes serve as "guiding bridges" that take viewers into the more profound psychological and emotional realms of his creations.

The viewers can gradually delve deeper and deeper with the help of these "guiding bridges". The idea of "life and death" is implied by the paintings, whether they are "Dance of Trees" or "Marron Hugger." The artist's contemplation of life's cycle and the essence of existence is suggested by the contrast between life and death. Numerous pieces by LU Song highlight the fine balance between life and death and affirm the fleeting nature of existence. He always illustrates various branches and leaves in a forest, for instance, withering and glorified, suggesting the fleeting nature of existence. In his works, death and life are frequently intimately associated with time's passage, reflecting both time's irreversibility and life's finiteness. The natural cycle of life is reflected in the growth, ageing, and regeneration of plants. In addition to being physical events, life and death are also emotional experiences. Life's joys and sorrows must be shown in order to accurately depict life and death.

The synthesis of "illusion" and "naturalism" in LU Song’s nature painting technique could be summed up as Phantasmal Naturalism, which captures the way he combines surreal feelings with natural components in his artwork. One of the most significant motifs in LU Song’s art is nature. His understanding and fascination with nature are evident in his observations, perceptions, and representations of plants. He produces a surreal visual experience and an enigmatic atmosphere by fusing matter and spirit, imagination and reality, such that the scenes in his paintings always have a transcendental aspect. In addition to displaying his accurate observations of nature, LU Song also combines his own spiritual ideas into his paintings.

Folding: Fragments of Thought

One of LU Song's creative focuses is painting technique research and experimentation. We are made aware of his paintings' conceptual quality by the Theatre series. LU Song recruited filmmakers, actors, models, choreographers, dancers, musicians, and other creatives to collaborate on the series, which began as a cross-border project in 2021. His initial goal was to use group production and improvisation to foster connections between individuals in various fields. LU Song retains the right to decide which portions of the image to remain, even if he does not use paints or take part in the actual painting process. He modifies the contributors' styles by manipulating the image's composition and utilising collage to combine the graffiti of two or three people to create a single, cohesive image. Since then, LU Song has also started to employ this method of image association in his studio works; the only difference is that he produces a new "theatre" by fusing images that he generates at various points in time to create a single image.

Undoubtedly, LU Song worked with innovators from other sectors in the early stages of this practice, a method that emphasises a strong sense of experimentation. By examining the hybrid state of disparate visual interests and modes of thought, he utilises painting as a means of fostering connections between individuals of various backgrounds. In order to fully unleash the randomness of painting, he rearranges and splices various pieces, producing unique visual results. LU Song must simultaneously make a number of thoughtful selections along the procedure. Additionally, this style expands the concept of painting to include a larger spectrum of artistic practices, challenging the idea that painting is only a visual art form. The painter's direct statement is changed into a deconstructed and rethought process of indirect, intentional editing and combination.

There is a fractured visual language in this series. This disarray is evident in both the way the text is presented and how the photos are organised. Together, the fragments create a rich and varied visual tale, with each fragment having its own distinct style and significance. His recognition of difference is reflected in the first method to cross-border cooperation, where each participant's distinct perspective and area of interest are made clear, and the result is a picture with layers and rich expressiveness. The disjointed visual language represents the multiplicity and intricacy of postmodern civilization, where many viewpoints, cultures, and values are continuously blending and clashing. The lack of a distinct main subject or sequential storyline in the photos allows for a multitude of interpretations and inspires viewers to use their imagination and own interpretation to explore the rich visual experience.

LU Song's emphasis on Theatre changed from outside cooperation to inward self-talk after 2022. He no longer gathers images through group cooperation like he did in the beginning; instead, he picks up and merges the images he generates in various states of flux, synthesising them into fragmented new images. This approach is a reflection of his integration and contemplation of his previous creations. By doing this, LU Song consistently improves his painting methods while revisiting the conceptual and haphazard aspects of the development of these pieces. Through working with artists from other disciplines, LU Song is exposed to a variety of viewpoints and passions. He has also improved his method of fusing form and substance through introspection, which has helped him understand a specific visual language.

Recent works by LU Song, such as "Dance of Trees," "Marron Hugger" and "Theatre," incorporate the imaginative justifications of language study, natural revelation, and spiritual inquiry. His creations investigate existence, time, and life. Painting becomes a bridge to investigate the mysteries of the psyche under his brush. His paintings poetically express the core of existence and the order of the world, much like philosophical dissertations do. On the canvas, the contemplation of life and the awareness of time are objectified into colours and shapes. LU Song’s paintings imply that life is not just a material journey but also a spiritual inquiry and a renewal of the look in a world full of miracles and transformations. As Michel Tournier stated in Friday, or, The Other Island, "The true journey of discovery is not to look for new sights, but to have new eyes."

-

XU Jin

CRITICS’ PICKSDON GALLERY 东画廊

Hall D, 2555 Longteng Avenue, West Bund, Shanghai, China

January 12–March 3, 2019“Everything Has a Soul” is not a theme but a spell that XU Jin has recited over the thirteen paintings in this exhibition. The silhouette of a man with a crow on his shoulder is visible in the foreground of The Last of Sunset, 2017, surrounded by skulls and carrion, and a dripping white sky on the verge of implosion. It’s a landscape, yes, but where? Or when?

XU is no newcomer—his career as an artist began in the mid-1970s as the Cultural Revolution was coming to an end. The playful figural elements of his earlier paintings are now gone, and his work is relentlessly earnest, with no trace of irony; even when he starts to draw an artist’s palette hovering like a spaceship in the sky in Artist Point in Yellowstone Park, 2018, he abandons it and returns us to a daunting landscape covered with snow and trees. He shares with the viewer a commitment to dwell with a scene—not just with one or two elements or characters, but with its core foundation.

XU paints as if everything has a soul that the world seeks to extinguish, and his works portray environments in which its characters seem to vacillate between the anticipation of action and its aftermath. The title piece of the exhibition, Everything Has a Soul, 2016, is a night scene awash in the phosphorescent glow of snow, semen, and fairies. A man stands witness, clutching a briefcase, expectant. Of all the paintings, this is Xu’s most ominous, its glowing organisms unleashing their frenzied thingness into our world.

-

胡子在刚刚结束于东画廊的展览“石肉”中构筑起两座“石”与一具“肉”的“对话域”(dialogic sphere):“石”所刻画的意大利雕塑海神(Neptune)、大卫(David)以及“肉”所描绘的英国乐手大卫·吉尔摩(Dav...

-

1:14 am Je n’aime que le mouvement —“What are the states of your being around 1:14 in the early morning?” —“In good states, live in God’s favour; i...

-

每当满潮时,河水暴涨,便出现逆流。观测站的信号旗显示出平稳的风速,朝着塔上飘去。在茫茫夜雾之中,海关的尖塔显得烟气迷蒙起来。堆放在堤坝上的木桶坐着许多苦力,他们的身上湿漉漉的。残破不堪的黑帆随着钝重的波涛东倒西歪地吱吱嘎嘎地向前移动。长着一张白皙明敏的中世纪勇士面孔的参木满街转悠之后回到了码头。河畔长条椅上坐着一排满脸倦容的俄国妓女。逆潮行驶的舢板上蓝色的灯光,在她们默默无语的眼睑...

-

QU Fengguo graduated from the Stage Design Department at Shanghai Theatre Academy and stayed to teach around the end of 1980s. As a backbone force in cultivating the presence of abstract paint...

-

On the occasion of the advent of ZHANG Yunyao’s solo exhibition “Skin Gesture Body,” Don Gallery looks back to the artist’s felt drawing in a new retrospective. The thr...

-

“Decoration” is the primary orientation for my artistic practice throughout the whole year of 2017. It will be comprised of 4 to 5 separate projects for spaces around differen...

-

约翰·伯格(John Berger)曾说:“我们注视的从来不只是事物本身,而是事物与我们之间的关系。”[1] 在吕松的绘画中,组成事物的“可见性”元素包括根、茎、叶、巨大的热带植物,比如芭蕉,以及纠缠其中的单一人物,或者是枝形吊灯、玻璃瓶、街道、建筑物。而这些事物与作为观察者、观看者的我们之间的关系通过其画面中特定的观看...